The threat of ransomware dominates the cyber news right now, and rightly so. But this week Rachael Falk, chief executive officer of Australia’s Cyber Security Cooperative Research Centre, made a very good point.

Ransomware is “totally foreseeable and preventable because it’s a known problem”, Falk told a panel discussion at the Australian Strategy Policy Institute (ASPI) on Tuesday.

“It’s known that ransomware is out there. And it’s known that, invariably, the cyber criminals get into organisations through stealing credentials that they get on the dark web [or a user] clicking on a link and a vulnerability,” she said.

“We’re not talking about some sort of nation-state really funky sort of zero day that’s happening. This is going on the world over, so it’s entirely foreseeable.”

There are “four or five steps you could take that could significantly mitigate this risk,” Falk said. These are patching, multi-factor authentication, and all the stuff in the Australian Signals Directorate’s Essential Eight baseline mitigation strategies.

The latest Essential Eight Maturity Model even comes with detailed checklists for Windows-based networks.

“Companies are on notice that this is a risk for them,” Falk said. “There’s a known problem often, and a known fix, but people haven’t done it.”

So given this laziness, given that cyber wake-up calls have been ignored since the 1970s, and given that organisations continue to willfully fail to follow the advice they’re given, your correspondent has a question.

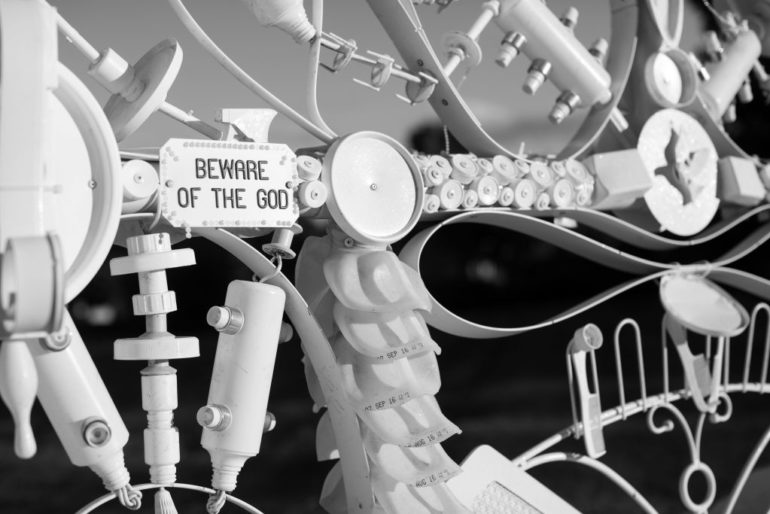

Has the time come to let Darwinism loose? Should we let all these lazy organisations get hacked, and just let God sort them out?

“I love that approach,” Falk said. “It is glacial-like movement, and I think the only change now that might accelerate it is legislation, which obviously government is potentially seeking to introduce at the moment,” she said, referring to proposed changes to critical infrastructure laws.

Maybe we’ll only start paying attention when there’s more 5G, more device-to-device communication, and more personal dependence on the network.

“I kind of wonder, though, in a macabre kind of way, will the test be when people just can’t use their phones for half an hour,” Falk said.

“That’s when you’ll get people going, oh, we just have to have law about this because we can’t cope with [no] iPhones, internet, fridge, streaming, Netflix, you name it.”

OK, we’re joking. Probably.

In cybersecurity as in public health, blaming the victim is counterproductive. And in many cases it’s the customers and citizens who’d really suffer from ransomware and other cyber attacks that take out an organisation.

“It could really, really impact life, and be a threat and risk to life. So I think people have to start thinking about this as not some sort of a joke,” Falk said.

“The fact that we joke about, oh, the internet being down for 30 minutes, it could be the matter of a medical procedure is stopped and someone dies halfway through.”

In Germany last year, for example, a patient died following a ransomware attack on a hospital in Duesseldorf, which caused her to be re-routed to a hospital more than 30 kilometres away. A police investigation found that she probably would have died anyway, but next time we may not be so lucky.

ASPI’s ransomware policy recommendations

Fortunately, a global consensus on how to tackle ransomware does seem to be emerging.

Just one example is a new report from ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre, Exfiltrate, encrypt, extort: The global rise of ransomware and Australia’s policy options, of which Falk is co-author.

On the vexed question of whether organisations should pay a ransom or not, the report recommends that paying them should not be criminalised. Instead, there should be a “mandatory reporting regime … without fear of legal repercussions”.

This would be a major step in transparency. Out of all the major ransomware incidents in Australia — Toll Holdings, BlueScope Steel, Lion Dairy and Drinks, legal document-management services firm Law in Order, Nine Entertainment, Eastern Health in Victoria, Uniting Care Qld, and JBS Foods — only JBS has admitted to paying a ransom of $11 million.

Such a scheme has already been proposed by Labor in its Ransomware Payments Bill 2021 introduced onto parliament last month as part of its national ransomware strategy.

The ASPI report recommends expanding the role of the ASD’s Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) to include the real-time distribution of publicly available alerts.

ACSC should also publish a list of ransomware threat actors and aliases, giving details of their modus operandi and key target sectors, along with suggested mitigation methods.

The ASD is already known to be using its classified capabilities to warn of impending ransomware attacks.

The report also recommends tackling the “low-hanging fruit” of incentivisation and education.

This includes incentives such as tax breaks for cyber investment, grants, or subsidy programs; a “concerted nationwide public ransomware education campaign, led by the ACSC, across all media”; and a “business-focused multi-media public education campaign”, also led by the ACSC.

“[This campaign should] educate organisations of all sizes and their people about basic cybersecurity and cyber hygiene. It should focus on the key areas of patching, multifactor authentication, legacy technology, and human error.”

Finally, the report recommends creating a “dedicated cross-departmental ransomware taskforce”, including state and territory representatives, to share threat intelligence and develop policy proposals.

Your correspondent finds none of these recommendations unreasonable, though there are perhaps questions about whether ACSC is currently well-equipped to run an effective and engaging major public information campaign.

Nevertheless, given how slowly Australian organisations have adapted to cyber risks over the last couple of decades, maybe we need a little less carrot and a bit more stick.