An encryption tool co-created by a University of Cincinnati math professor will soon safeguard the telecommunications, online retail and banking and other digital systems we use every day.

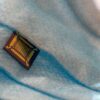

The National Institute of Standards and Technology chose four new encryption tools designed to thwart the next generation of hackers or thieves. One of them, called CRYSTALS-Kyber, is co-created by UC College of Arts and Sciences math professor Jintai Ding.

“It’s not just for today but for tomorrow,” Ding said. “This is information that you don’t want people to know even 30 or 50 years from now.”

Ding’s algorithm was designed to withstand probing from quantum computers, which harness the power of quantum mechanics to speed calculations. The faster the calculations, the more quickly a security system can be breached.

“Given enough time, you can decrypt any system,” Ding said. “But if it takes 10,000 years, nobody cares.”

The institute, part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, selected CRYSTALS-Kyber among three other tools.

Symmetric encryption uses math to protect sensitive electronic information, from the texts we send to financial documents we share. Public-key systems help the sender and receiver to create a shared secret key, which is used to encrypt and decipher data to deter uninvited third parties.

“The implications are very profound,” Ding said. “Without a modern encryption system, we don’t have the internet. We don’t have secure communications. No online banking. No software updates. Our whole digital society relies on modern cryptography.”

Among the advantages NIST cited for CRYSTALS-Kyber was its efficiency.

“It can’t be too slow,” Ding said. “You don’t want lag time. You want to read your message immediately.”

Likewise, you don’t want the encryption to take up valuable computer storage.

The federal agency also chose three algorithms to verify people’s identities during digital transactions.

“The sister of Kyber is called Dilithium, which is used for authentication. They’re used together sometimes and sometimes they’re used separately,” Ding said.

The names might ring familiar to fans of “Star Trek” and “Star Wars.” Kyber crystals power lightsabers while dilithium crystals power the warp drive of the USS Enterprise. Ding credited his collaborators for the colorful names.

“Encryption is not as easy to understand as ‘Star Wars,'” he joked.

The need for improved cybersecurity can’t be overstated, said Richard Harknett, chairman of UC’s Center for Cyber Strategy and Policy.

“Quantum technology has the potential to undermine the fundamentals of how we securely exchange digital data,” Harknett said. “Professor Jintai Ding has been a leader in this field for decades and has worked consistently to solve this looming threat. He and his team have provided NIST with a solution that will benefit global security.

“We are fortunate to have Dr. Ding, whose vision has driven cryptography to a new level. UC talks about next lives here. Dr. Ding has proven it does.”

The standards adopted by the United States often become the de facto standards around the world, Ding said. So the new cybersecurity could have far-reaching implications.

Ding took a circuitous route to studying cryptography. His expertise as a tenured professor of math at UC was in quantum algebra. But in 2001, he read about a quantum computer created by MIT physicist Isaac Chuang.

“I was amazed. I immediately realized that we have to replace all the existing key code systems protecting our data,” he said. “I gave up what I was doing and switched to cryptography. UC gave me a lot of support.”

Implementing the new security is expected to take years because it’s not as easy as installing a software patch. But its protections could last for a generation.

Even as encryption tools get more powerful, others are working on new attacks to crack them.

“This is a game we’ll keep playing,” Ding said. “We can never be complacent.”

Provided by

University of Cincinnati

Citation:

New encryption tool is designed to thwart quantum computers (2022, August 26)