Cleaning up legacy radioactive waste from nuclear weapons production has been a daunting, lengthy, and expensive process.

Now, researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) have designed and demonstrated a simple particle separation technology that may decrease the time and money needed for cleanup. The industrial-scale application is described in Chemical Engineering and Processing—Process Intensification.

What’s more, the technology may have broad industrial uses, including in food processing, advanced manufacturing, aerosol science, supercritical fluids, oil and gas, and environmental waste processing.

If the particle fits

Nuclear waste cleanup is complicated. For the radioactive and chemical waste, such as that stored in underground tanks at the Hanford Site, it may benefit the treatment process to separate the raw solid and liquid waste by particle size.

In PNNL testing of simulated waste—in this case, buckets of granular oxides mixed with water into a slurry—the newly developed separation technology quickly and successfully separated larger particles from smaller ones at various scales with several different solid-liquid mixtures.

The bench-scale demonstration maintained 94 percent flow over seven hours with no work stoppage from clogging. Further, the tests worked at a rate of 90 gallons per minute through a three-inch pipe, which is an optimal flow for industrial operations.

“That 90 gallons per minute flow rate was the number needed for potential industry applications, and faster flow rates are achievable,” said Leonard Pease, the lead inventor and a chemical engineer at PNNL. In most research settings, said Pease, you can design the concept and maybe complete a lab-scale test or two in one year. But PNNL had the right facilities and right people for the project to jump quickly to full-scale.

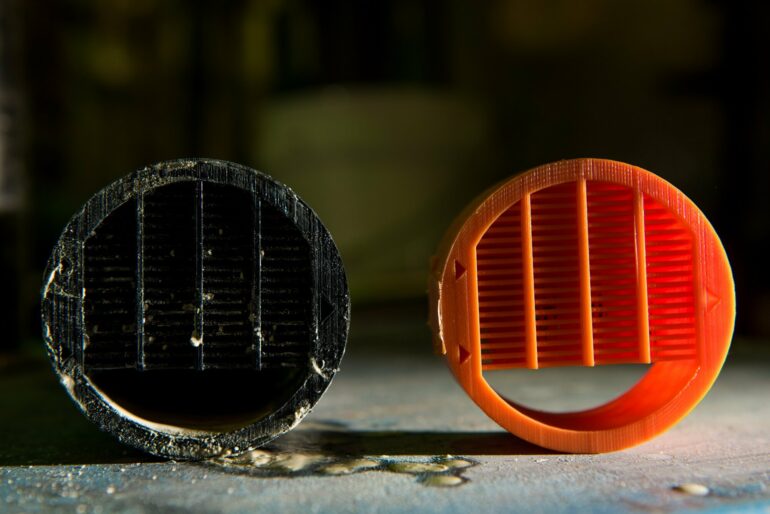

Michael Minette shows 300-micron and larger particles separated out of a slurry mixture using Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s mesofluidic separator. These results came from tests on simulant at PNNL’s Multi-Phase Transport Evaluation Laboratory. © Andrea Starr | Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Particle pachinko

The cleverly designed separation system resembles a series of hollow hockey pucks filled with rows of individual posts. Each row of descending posts is slightly offset from the row above. The team nicknamed it “pachinko” due to its resemblance to the popular game used at carnivals and on television game shows.

With the fluid stream moving at speeds up to 90 gallons per minute, the posts create unique flow fields that cause larger particles to move in the desired direction. Researchers have created “express lanes” within the system to remove larger particles. The novel post layout is a major improvement for turbulent flows.

In a full-scale system, multiple sets of pucks with different post designs will guide particles to their own express lane, separating relatively large pieces (about 1 centimeter or the size of a lemonhead candy) down to 20 microns (about the size of a white blood cell). By stacking pucks one behind another, “you gain economies of scale without adding more costly infrastructure,” said Pease. The separator works in both horizontal and vertical mode, including top-down and bottom-up flows, Pease added.

Brainstorming bumps

Inspired by bump arrays used in the medical field, Pease and colleagues Michael Minette and Carolyn Burns knew that large particles could be separated out of process streams at very low flow rates, but the process had not yet been demonstrated at high flow rates.

A small, slow stream—called laminar flow—is calm, steady, and predictable. As the flow becomes larger and faster—called turbulent flow—it starts to swirl.

They thought they would have to stick with laminar flow to keep the particles in the correct lanes. In a 3-inch steel pipe—common for nuclear waste operations—that would restrict the flow rate to under five gallons per minute, which is not ideal. Running under turbulent conditions was the only way to achieve the desired operational flow rates.

So, the team members designed their initial device to work in a vertical pipe. They expected an arduous design process to overcome turbulent flow issues. They were wrong.

“Conventional wisdom said the system would work only on a smooth, laminar flow, but we proved it also works on turbulent flow,” Minette said.

The success in turbulent flow conditions led the team to the concept of flow-following dynamics, Minette said. “We realized that most of the larger particles were not bouncing off of posts, but were being driven by flow streams created by the posts.”

In this design, the posts create flow streams that direct large particles to the express lane so they can be removed—greatly reducing erosion of the pins and extending the life of the devices, said Burns, a chemical engineer who scaled-up the laboratory experiments.

“I was amazed that the pins didn’t break and erode—they held up to the flow and the aggressive materials,” Burns said. “This experimental evidence was a major advance in the functionality of the system.”

More information:

Leonard F. Pease et al, Industrial scale mesofluidic particle separation, Chemical Engineering and Processing—Process Intensification (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cep.2022.108795

Provided by

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

Citation:

Size matters for speeding up nuclear waste cleanup (2022, May 12)