Quantum computing is bright and shiny, with demonstrations by Google suggesting a kind of transcendent ability to scale beyond the heights of known problems.

But there’s a real bummer in store for anyone with their head in the clouds: All that glitters is not gold, and there’s a lot of hard work to be done on the way to someday computing NP-hard problems.

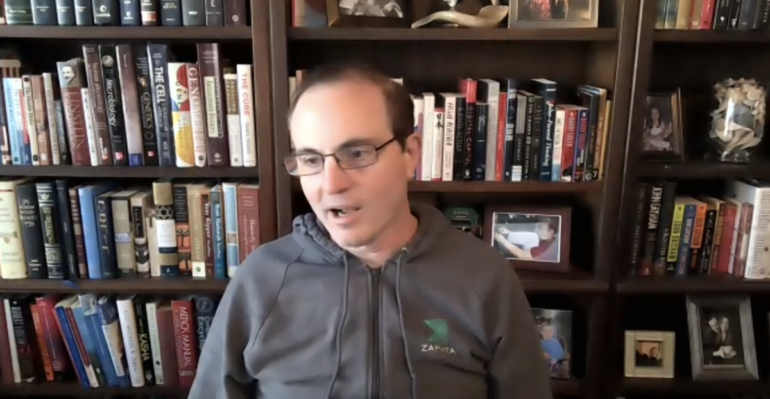

“ETL, if you get that wrong in this flow-based programming, if you get the data frame wrong, it’s garbage in, garbage out,” according to Christopher Savoie, who is the CEO and a co-founder of three-year-old startup Zapata Computing of Boston, Mass.

“There’s this naive idea you’re going to show up with this beautiful quantum computer, and just drop it in your data center, and everything is going to be solved — it’s not going to work that way,” said Savoie, in a video interview with ZDNet. “You really have to solve these basic problems.”

“There’s this naive idea you’re going to show up with this beautiful quantum computer, and just drop it in your data center, and everything is going to be solved — it’s not going to work that way,” said Savoie, in a video interview with ZDNet. “You really have to solve these basic problems.”

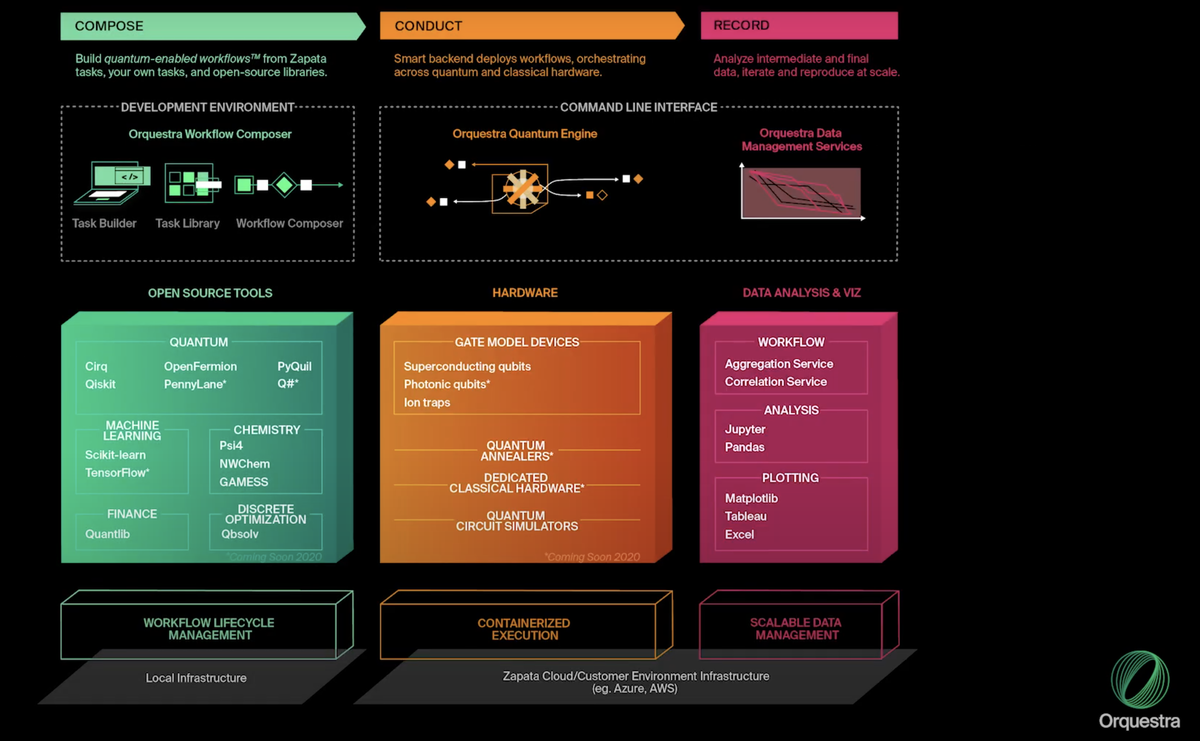

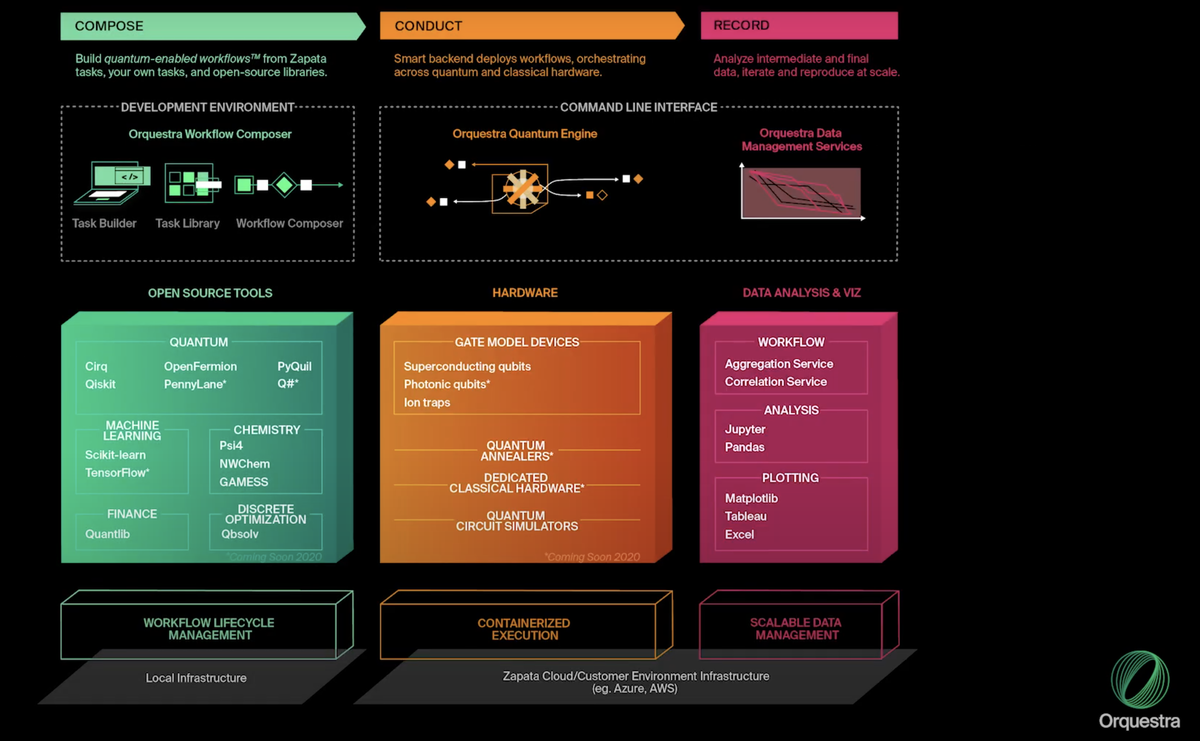

Zapata sells a programming tool for quantum computing, called Orquestra. It can let developers invent algorithms to be run on real quantum hardware, such as Honeywell’s trapped-ion computer.

But most of the work of quantum today is not writing pretty algorithms, it’s just making sure data is not junk.

“Ninety-five percent of the problem is data cleaning,” Savoie told ZDNet in a video interview. “There wasn’t any great toolset out there, so that’s why we created Oquestra to do this.”

The company on Thursday announced it has received a Series B round of investment totaling $38 million from large investors that include Honeywell’s venture capital outfit, and returning Series A investors Comcast Ventures, Pitango and Prelude Ventures, among others. The company has now raised $64.4 million.

Also: Honeywell introduces quantum computing as a service with subscription offering

Zapata was spun out of Harvard University in 2017 by scholars including Alán Aspuru-Guzik, who has done fundamental work on quantum. But a lot of what is coming up are the mundane matters of data prep and other gotchas that can be a nightmare in a bold new world of only partially-understood hardware.

Things such as extract, transform, load, or ETL, that become maddening when prepping a quantum workload.

“We had a customer who thought they had a compute problem, because they had a job that was taking a long time; it turned out, when we dug in, just parallelizing the workflow, the ETL, gave them a compute advantage,” recalled Savoie.

Such pitfalls are things, said Savoie, that companies don’t know are an issue until they get ready to spend valuable time on a quantum computer and code doesn’t run as expected.

“That’s why we think it’s critical for companies to start now,” he said, even though today’s noisy intermediate-scale quantum, or NISQ, machines have only a handful of qubits.

“You have to solve all these basic problems we really haven’t even solved yet in classical computing,” said Savoie.

The present moment in time in the young field of quantum sounds a bit like the early days of micro-computer based relational databases. And, in fact, Savoie likes to make an analogy to the era of the 1980s and 1990s, when Oracle database was taking over workloads from IBM’s DB/2.

Also: What the Google vs. IBM debate over quantum supremacy means

“Oracle is a really good analogy, he said. “Recall when SQL wasn’t even a thing, and databases had to be turned on a per-on-premises, as-a-solution basis; how do I use a database versus storage, and there weren’t a lot of tools for those things, and every installment was an engagement, really,” recalled Savoie.

“There are a lot of close analogies to that” with today’s quantum, said Savoie. “It’s enterprise, it’s tough problems, it’s a lot of big data, it’s a lot of big compute problems, and we are the software company sitting in the middle of all that with a lot of tools that aren’t there yet.”

Mind you, Savoie is a big believer in quantum’s potential, despite pointing out all the challenges. He has seen how technologies can get stymied, but also how they ultimately triumph. He helped found startup Dejima, one of the companies that became a component of Apple’s Siri voice assistant, in 1998. Dejima didn’t produce an AI wave, it sold out to database giant Sybase.

“We invented this natural language understanding engine, but we didn’t have the great SpeechWorks engine, we didn’t have 3G, never mind 4G cell phones, or OLED displays,” he recalled. “It took ten years from 1998 till it was a product, till it was Siri, so I’ve seen this movie before — I’ve been in that movie.”

But the technology of NLP did survive and is now thriving. Similarly, the basic science of quantum, as with the basic science of NLP, is real, is validated. “Somebody is going to be the iPhone” of quantum, he said, although along the way there may be a couple Apple Newtons, too, he quipped.

Even an Apple Newton of quantum will be a breakthrough. “It will be solving real problems,” he said.

Also: All that glitters is not quantum AI

In the meantime, handling the complexity that’s cropping up now, with things like ETL, suggests there’s a roll for a young company that can be for quantum what Oracle was for structured query language.

“You build that out, and you have best practices, and you can become a great company, and that’s what we aspire to,” he said.

Zapata has fifty-eight employees and has had contract revenue since its first year of operations, and has doubled each year, said Savoie.