Tech firms have spent years hawking the idea of a connected home filled with “smart” devices that help smooth daily domestic lives—and this year’s CES gadget show in Las Vegas is no different.

The world’s biggest tech trade show features everything from televisions that ping when your clothes dryer is done, to mirrors that fire up your coffee machine in the morning.

But the vision on display at CES remains far from reality as the devices are pricey and they do not yet talk to each other with any fluency.

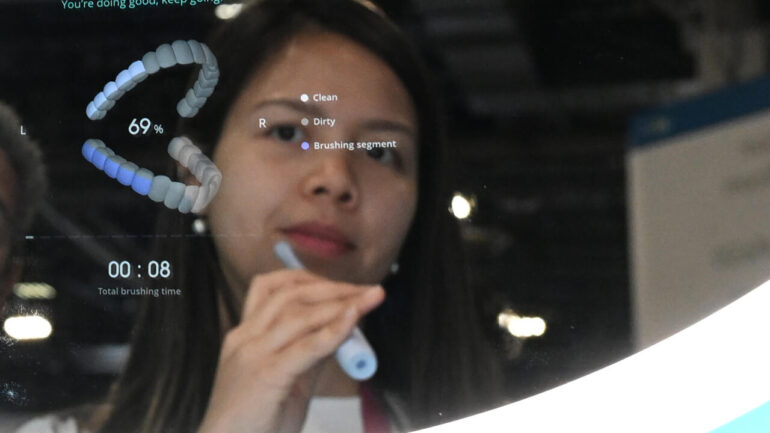

French company Baracoda is at CES, which runs from 5 to 8 January, to show off a prototype connected mirror that can interact with bathroom scales, the toilet or a toothbrush.

“You can see immediately if you’ve brushed your teeth properly or if you need to put on sunscreen, for example,” says the firm’s Baptiste Quiniou.

But it can only work to its full capacity with devices developed by Baracoda or its partners.

For start-ups and multinationals, making these products work with other brands is becoming crucial.

“Sometimes they can do incredibly useful things, but if they’re not connected to the wider info system, information dies alone,” said analyst Avi Greengart.

Battle of ecosystems

Big players from Amazon and Apple to Google and Samsung have built entire ecosystems for their devices, often around a voice assistant like Alexa or Siri.

Samsung is pushing its Smart Things app as the best way to control a connected home.

Greengart said each company thought its ecosystem would draw in enough people and devices to dominate the others.

“What ended up happening is that nobody grew,” he said, and the industry “to an extent stagnated”.

The biggest firms have spent years trying to tackle the “interoperability” problem, finally agreeing a protocol last year called “Matter” that sets a standard for connected home products.

“You can think about it as the USB of the smart home,” said Mark Benson of Smart Things, Samsung’s connected home subsidiary.

Just as USB ports allowed all devices to plug into all machines, so the Matter protocol means all connected devices will work with each other, he said, and users will no longer need to download a different app for each device.

But Matter will not kill off Alexa, Siri and their friends just yet.

Jeff Wang of Accenture said making the devices work with each other was the easier part.

“The hard part is the app model, the data model, the sharing of this, because the human nature of companies is to be very selfish about this,” he said.

Each brand is now trying to convince the public to adopt its app to centralize control of household appliances.

At CES, Samsung presented a vision of consumers using its Smart Things app to monitor the chicken in the Samsung oven while watching a Samsung TV that would also tell them when their Samsung washing machine was finishing its cycle.

Google showed how home devices could easily be linked up with its mobile app.

The last ‘smart’ device

Mark Benson reckoned more than half of homes in America now have a smart device in them.

“And more than half of those started their smart home journey just in the last three years,” he said.

Yet for now, consumers have largely limited their buy-in to the connected home to inexpensive “smart” speakers, using them as timers or to listen to music.

A spokesperson for CTA, the industry body that organizes CES, said connected home devices were facing “a tough year in the US because of the decline in home sales”.

But CTA reckoned the Matter standard would drive the connected home market as the housing sector recovers.

The association said in particular sales of devices that promise to help save energy were likely to go up this year.

It predicted that almost 5 million connected thermostats would be sold in 2023, up 15 percent year-on-year.

In the same field, US company Savant has designed a connected fuse box that will help people monitor energy use.

“That’s maybe one of the last, forgotten, things in the home that can be made smart,” said Ian Roberts, a group vice president.

2023 AFP

Citation:

The oven won’t talk to the fridge: ‘smart’ homes struggle (2023, January 6)