Scientists are seeing the Australian platypus in a whole new light. Under an ultraviolet lamp, this bizarre-looking creature appears even more peculiar than normal, glowing a soft, greenish-blue hue instead of the typical brown we’re used to seeing.

The recent discovery has not been found in any other monotreme species – a primitive type of mammal – and it has scientists wondering: Have we been overlooking an ancient world of fluorescent fur?

“Biofluorescence has now been observed in placental New World flying squirrels, marsupial New World opossums, and the monotreme platypus of Australia and Tasmania,” the authors write.

“These taxa, inhabiting three continents and a diverse array of ecosystems, represent the major lineages of Mammalia.”

(Anich et al., Mammalia, 2020)

Over the centuries, biofluorescence has been reported in various plants, fungi, fruits, flowers, insects, and birds. It’s only recently, however, that scientists have begun to actively track down examples in the animal kingdom. Many discoveries to date were simply happenstance.

In 2015, for instance, scientists chanced upon the first fluorescent sea turtle while looking for glowing coral. Two years later, the first fluorescent frog was found unexpectedly, and the team advised others to “start carrying a UV flashlight to the field”.

Among mammals, the first example of biofluorescence was reported in 1983 in the Virginia opossum, the only marsupial in North America. But it wasn’t until 2017, and by complete accident, that researchers uncovered something similar in North America’s flying squirrels (Glaucomys), which are categorized as placental mammals.

While conducting a night survey of lichens, researchers were amazed to turn their LED torch on a bright, bubble-gum pink flying squirrel.

One of the only things the opossum and squirrel share in common is their nocturnal lifestyles. This is also when UV light is at its strongest, which suggests the trait might be common among mammals most active at night, dawn, or dusk.

Like flying squirrels and opossums in North America, platypuses in Australia are also active at night. However, they are separated from these other animals by some 150 million years of evolution.

Australia’s hidden glows

Despite being home to some of the most primitive mammals on Earth, relatively little attention has been paid to biofluorescence in Australia’s animals. But if they also have glowing fur, the trait might be far more ancient and potentially more common among mammals than we thought.

“It was a mix of serendipity and curiosity that led us to shine a UV light on the platypuses at the Field Museum,” recalls biologist Paula Spaeth Anich from Northland College.

“But we were also interested in seeing how deep in the mammalian tree the trait of biofluorescent fur went.”

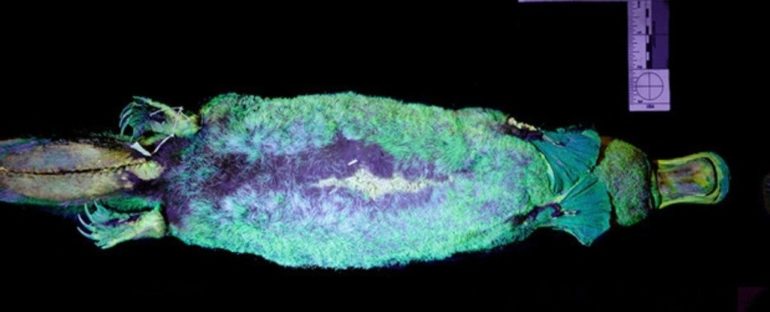

Researchers began with two stuffed museum specimens, a male and a female collected in Tasmania. These creatures’ fur was found to absorb short UV wavelengths and then emit visible light, fluorescing green or cyan.

Examining another platypus specimen collected from New South Wales, researchers found the same thing.

“The pelage of this specimen, which was uniformly brown under visible light, also biofluoresced green under UV light,” the authors write.

To their knowledge, the team says this is the first time biofluorescence has been reported in monotremes. However, in June of this year, a member of The Queensland Mycological Society claimed to have discovered a road-killed platypus with a similar glow.

“The fur of the platypus mostly appeared dark/purple as expected under the UV light, but some of it turned moss green, although not brightly so,” writes Linda Reinhold in the society’s non-peer-reviewed newsletter.

Reinhold also found two northern brown bandicoots on the road with fluorescent pink fur, and she did manage to snap those.

Lighting up the dark

It’s still too early to say what advantage this trait might give nocturnal mammals – our sample sizes are too small – although scientists have a few ideas.

In 2017, when the flying squirrels were discovered with biofluorescent fur, some thought it might have to do with camouflage since many trees are covered in biofluorescent moss and lichen.

However, the bandicoots found by Reinhold are ground-dwelling mammals, and their fluorescence may make them stand out.

Standing out might be an advantage, depending on the circumstances. For some birds, their biofluorescent feathers play a part in mating rituals. Fish use the trait to communicate among themselves.

Yet in the platypus, both the male and female specimens showed similar fluorescence, suggesting the trait isn’t sexually dimorphic. What’s more, because the platypus usually swims with its eyes closed, the glow in its fur probably isn’t there to communicate with others of its kind.

Instead, researchers think it might help camouflage the platypus from other UV-sensitive nocturnal predators by absorbing UV light instead of reflecting it.

Further study is needed in the wild before we can say for sure what is going on. We don’t even know how the biofluorescence of this fur even works, and the benefits of this trait might vary from species to species.

Still, the fact that this strange glow exists across the fur of egg-laying monotremes, marsupials, and placental mammals suggests it has deep roots.

If nothing else, the discovery is a nice reminder of our sheer ignorance.

The study was published in Mammalia.