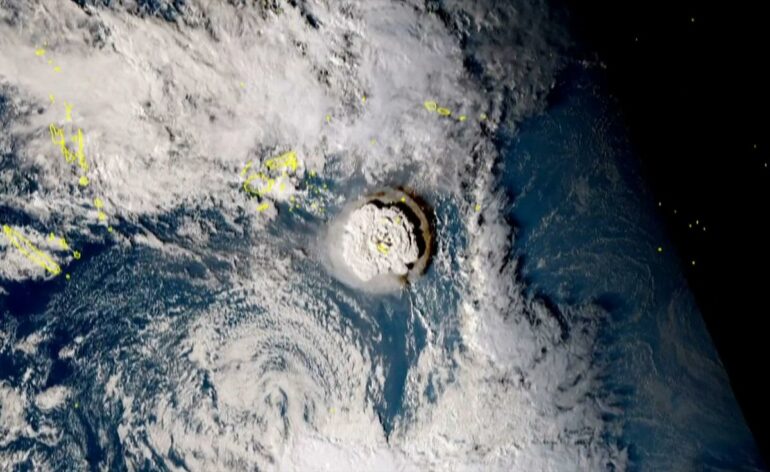

The Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption reached an explosive crescendo on Jan. 15, 2022. Its rapid release of energy powered an ocean tsunami that caused damage as far away as the U.S. West Coast, but it also generated pressure waves in the atmosphere that quickly spread around the world.

The atmospheric wave pattern close to the eruption was quite complicated, but thousands of miles away it appeared as an isolated wave front traveling horizontally at over 650 miles an hour as it spread outward.

NASA’s James Garvin, chief scientist at the Goddard Space Flight Center, told NPR the space agency estimated the blast was around 10 megatons of TNT equivalent, about 500 times as powerful as the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, during World Word II. From satellites watching with infrared sensors above, the wave looked like a ripple produced by dropping a stone in a pond.

Satellite infrared observations captured the pulse propagating around the world.

Mathew Barlow/University of Massachusetts Lowell

The pulse registered as perturbations in the atmospheric pressure lasting several minutes as it moved over North America, India, Europe and many other places around the globe. Online, people followed the progress of the pulse in real time as observers posted their barometric observations to social media. The wave propagated around the whole world and back in about 35 hours.

I am a meteorologist who has studied the oscillations of the global atmosphere for almost four decades. The expansion of the wave front from the Tonga eruption was a particularly spectacular example of the phenomenon of global propagation of atmospheric waves, which has been seen after other historic explosive events, including nuclear tests.

This eruption was so powerful it caused the atmosphere to ring like a bell, though at a frequency too low to hear. It’s a phenomenon first theorized over 200 years ago.

Krakatoa, 1883

The first such pressure wave that attracted scientific attention was produced by the great eruption of Mount Krakatoa in Indonesia in 1883.

The Krakatoa wave pulse was detected in barometric observations at locations throughout the world. Communication was slower in those days, of course, but within a few years, scientists had combined the various individual observations and were able to plot on a world map the propagation of the pressure front in the hours and days after the eruption.

The wave front traveled outward from Krakatoa and was observed making at least three complete trips around the globe. The Royal Society of London published a series of maps illustrating the wave front’s propagation in a famous 1888 report on the eruption.

Maps from an 1888 report, shown here as an animated loop, reveal the position every two hours of the pressure wave from the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa.

Kevin Hamilton, based on Royal Society of London images, CC BY-ND

The waves seen…