If you look back at the history of Atlantic hurricanes since the late 1800s, it might seem hurricane frequency is on the rise.

The year 2020 had the most tropical cyclones in the Atlantic, with 31, and 2021 had the third-highest, after 2005. The past decade saw five of the six most destructive Atlantic hurricanes in modern history.

Then a year like 2022 comes along, with no major hurricane landfalls until Fiona and Ian struck in late September. The Atlantic hurricane season, which ends Nov. 30, had eight hurricanes and 14 named storms in all. It’s a reminder that small sample sizes can be misleading when assessing trends in hurricane behavior. There is so much natural variability in hurricane behavior year to year and even decade to decade that we need to look much further back in time for the real trends to come clear.

Fortunately, hurricanes leave behind telltale evidence that goes back millennia.

Two thousand years of this evidence indicates that the Atlantic has experienced even stormier periods in the past than we’ve seen in recent years. That’s not good news. It tells coastal oceanographers like me that we may be significantly underestimating the threat hurricanes pose to the Caribbean and U.S. coasts in the future.

The natural records hurricanes leave behind

When a hurricane nears land, its winds whip up powerful waves and currents that can sweep coarse sands and gravel into marshes and deep coastal ponds, sinkholes and lagoons.

Under normal conditions, fine sand and organic matter like leaves and seeds fall into these areas and settle to the bottom. So when coarse sand and gravel wash in, a distinct layer is left behind.

Imagine cutting through a layer cake – you can see each layer of frosting. Scientists can see the same effect by plunging a long tube into the bottom of these coastal marshes and ponds and pulling up several meters of sediment in what’s known as a sediment core. By studying the layers in sediment, we can see when coarse sand appeared, suggesting an extreme coastal flood from a hurricane.

With these sediment cores, we have been able to document evidence of Atlantic hurricane activity over thousands of years.

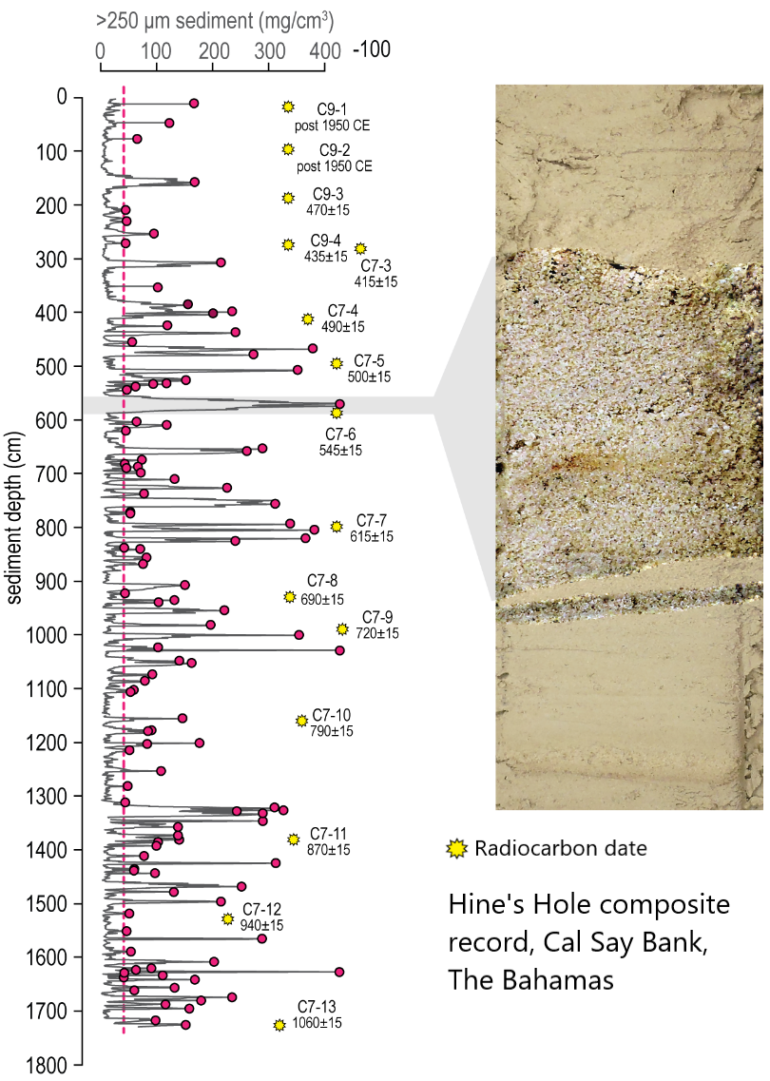

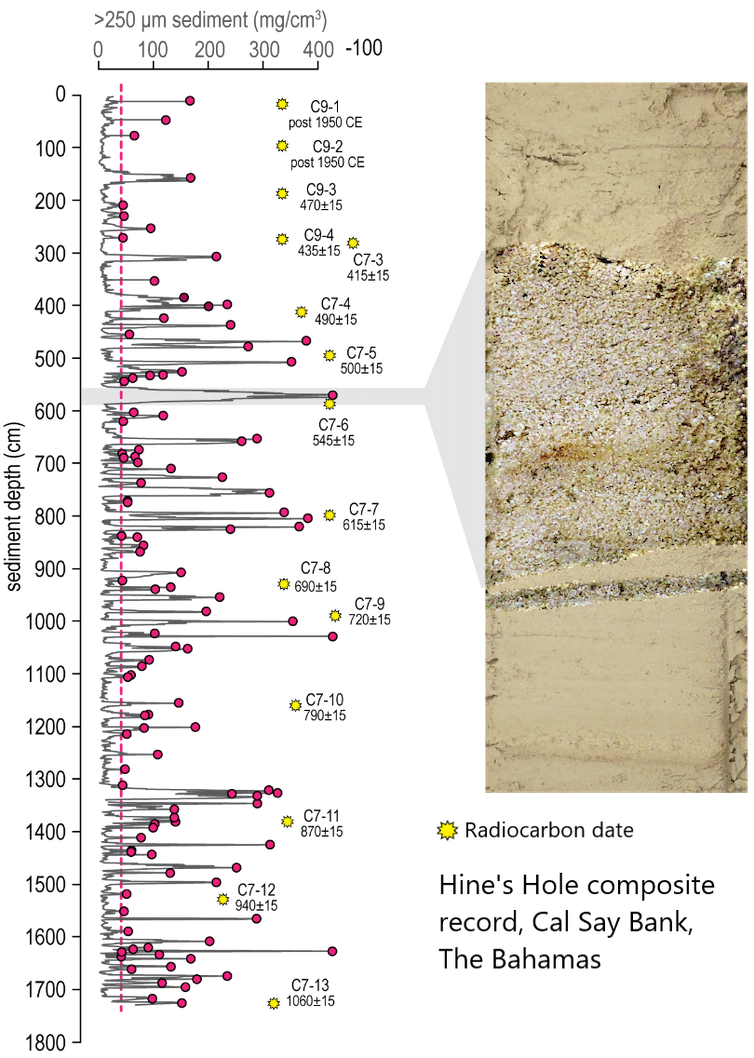

The red dots indicate large sand deposits going back about 1,060 years. The yellow dots are estimated dates from radiocarbon dating of small shells.

Tyler Winkler

We now have dozens of chronologies of hurricane activity at different locations – including New England, the Florida Gulf Coast, the Florida Keys and Belize – that reveal decade- to century-scale patterns in hurricane frequency.

Others, including from Atlantic Canada, North Carolina, northwestern Florida, Mississippi and Puerto Rico, are lower-resolution, meaning it is nearly impossible to discern individual hurricane layers deposited within decades of one another. But they can be highly informative for determining the timing of the most intense hurricanes, which can have significant…