Researchers at MIT have made significant steps toward creating robots that could practically and economically assemble nearly anything, including things much larger than themselves, from vehicles to buildings to larger robots.

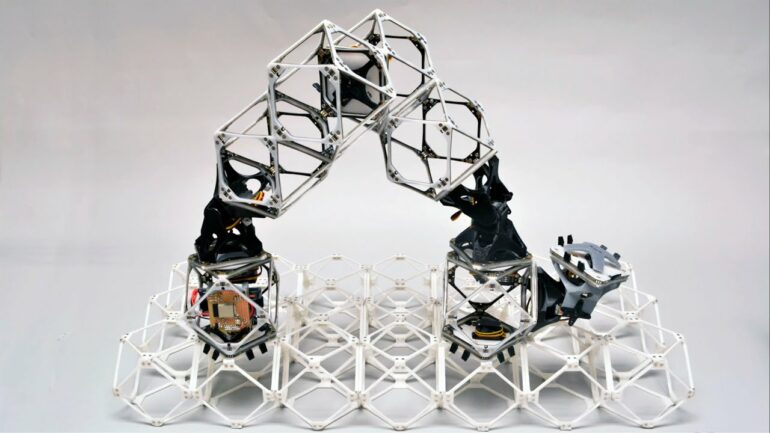

The new work, from MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA), builds on years of research, including recent studies demonstrating that objects such as a deformable airplane wing and a functional racing car could be assembled from tiny identical lightweight pieces—and that robotic devices could be built to carry out some of this assembly work. Now, the team has shown that both the assembler bots and the components of the structure being built can all be made of the same subunits, and the robots can move independently in large numbers to accomplish large-scale assemblies quickly.

The new work is reported in the journal Nature Communications Engineering, in a paper by CBA doctoral student Amira Abdel-Rahman, Professor and CBA Director Neil Gershenfeld, and three others.

A fully autonomous self-replicating robot assembly system capable of both assembling larger structures, including larger robots, and planning the best construction sequence is still years away, Gershenfeld says. But the new work makes important strides toward that goal, including working out the complex tasks of when to build more robots and how big to make them, as well as how to organize swarms of bots of different sizes to build a structure efficiently without crashing into each other.

As in previous experiments, the new system involves large, usable structures built from an array of tiny identical subunits called voxels (the volumetric equivalent of a 2D pixel). But while earlier voxels were purely mechanical structural pieces, the team has now developed complex voxels that each can carry both power and data from one unit to the next. This could enable the building of structures that can not only bear loads but also carry out work, such as lifting, moving and manipulating materials—including the voxels themselves.

“When we’re building these structures, you have to build in intelligence,” Gershenfeld says. While earlier versions of assembler bots were connected by bundles of wires to their power source and control systems, “what emerged was the idea of structural electronics—of making voxels that transmit power and data as well as force.” Looking at the new system in operation, he points out, “There’s no wires. There’s just the structure.”

The robots themselves consist of a string of several voxels joined end-to-end. These can grab another voxel using attachment points on one end, then move inchworm-like to the desired position, where the voxel can be attached to the growing structure and released there.

Gershenfeld explains that while the earlier system demonstrated by members of his group could in principle build arbitrarily large structures, as the size of those structures reached a certain point in relation to the size of the assembler robot, the process would become increasingly inefficient because of the ever-longer paths each bot would have to travel to bring each piece to its destination.

At that point, with the new system, the bots could decide it was time to build a larger version of themselves that could reach longer distances and reduce the travel time. An even bigger structure might require yet another such step, with the new larger robots creating yet larger ones, while parts of a structure that include lots of fine detail may require more of the smallest robots.

As these robotic devices work on assembling something, Abdel-Rahman says, they face choices at every step along the way: “It could build a structure, or it could build another robot of the same size, or it could build a bigger robot.” Part of the work the researchers have been focusing on is creating the algorithms for such decision-making.

“For example, if you want to build a cone or a half-sphere,” she says, “how do you start the path planning, and how do you divide this shape” into different areas that different bots can work on? The software they developed allows someone to input a shape and get an output that shows where to place the first block, and each one after that, based on the distances that need to be traversed.

There are thousands of papers published on route-planning for robots, Gershenfeld says. “But the step after that, of the robot having to make the decision to build another robot or a different kind of robot—that’s new. There’s really nothing prior on that.”

While the experimental system can carry out the assembly and includes the power and data links, in the current versions the connectors between the tiny subunits are not strong enough to bear the necessary loads. The team, including graduate student Miana Smith, is now focusing on developing stronger connectors.

“These robots can walk and can place parts,” Gershenfeld says, “but we are almost—but not quite—at the point where one of these robots makes another one and it walks away. And that’s down to fine-tuning of things, like the force of actuators and the strength of joints. … But it’s far enough along that these are the parts that will lead to it.”

Ultimately, such systems might be used to construct a wide variety of large, high-value structures. For example, currently the way airplanes are built involves huge factories with gantries much larger than the components they build, and then “when you make a jumbo jet, you need jumbo jets to carry the parts of the jumbo jet to make it,” Gershenfeld says. With a system like this built up from tiny components assembled by tiny robots, “The final assembly of the airplane is the only assembly.”

Similarly, in producing a new car, “you can spend a year on tooling” before the first car gets actually built, he says. The new system would bypass that whole process. Such potential efficiencies are why Gershenfeld and his students have been working closely with car companies, aviation companies, and NASA. But even the relatively low-tech building construction industry could potentially also benefit.

While there has been increasing interest in 3D-printed houses, today those require printing machinery as large or larger than the house being built. Again, the potential for such structures to instead be assembled by swarms of tiny robots could provide benefits. And the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is also interested in the work for the possibility of building structures for coastal protection against erosion and sea level rise.

Aaron Becker, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Houston, who was not associated with this research, calls this paper “a home run—[offering] an innovative hardware system, a new way to think about scaling a swarm, and rigorous algorithms.”

Becker adds: “This paper examines a critical area of reconfigurable systems: how to quickly scale up a robotic workforce and use it to efficiently assemble materials into a desired structure. … This is the first work I’ve seen that attacks the problem from a radically new perspective—using a raw set of robot parts to build a suite of robots whose sizes are optimized to build the desired structure (and other robots) as fast as possible.”

More information:

Amira Abdel-Rahman et al, Self-replicating hierarchical modular robotic swarms, Communications Engineering (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s44172-022-00034-3

Provided by

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This story is republished courtesy of MIT News (web.mit.edu/newsoffice/), a popular site that covers news about MIT research, innovation and teaching.

Citation:

Flocks of assembler robots show potential for making larger structures (2022, November 22)