Three species of shark that inhabit the twilit depths of the ocean just turned out to have been bioluminescent this whole time.

The kitefin shark, the blackbelly lanternshark, and the southern lanternshark have all been discovered to have softly glowing blue patterns on their skin, a first for sharks found in New Zealand waters.

Of those three, the kitefin shark, which grows up to 180 centimetres (5 feet 11 inches) long, is now the largest known bioluminescent shark in the world.

Bioluminescence is not an uncommon trait for living things to evolve. Even humans glow (although too faintly to actually see). It seems to be most useful for life forms that live in the dark – night-glowing fungus, insects in dark caves… and in the depths of the ocean, so deep that the rays of the Sun can’t penetrate the water.

In the mesopelagic, also known as the twilight zone, between 200 and 1,000 metres (650 and 3,300 feet) below the surface, bioluminescence is practically a way of life. It has been estimated that over 90 percent of all mesopelagic animals have some form of bioluminescence that they use in different ways.

In sharks, however, bioluminescence is not well-documented, nor extensively studied. Marine biologists Jérôme Mallefet and Laurent Duchatelet of the Université catholique de Louvain in Belgium have been leading an effort to redress this.

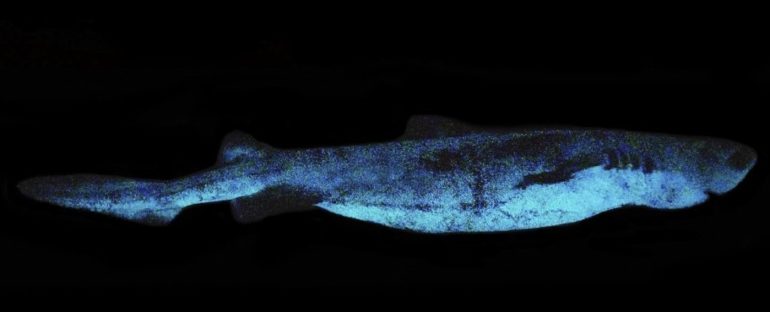

The kitefin shark glow pattern. (Mallefet et al., Front. Mar. Sci., 2021)

“Bioluminescence has often been seen as a spectacular yet uncommon event at sea,” the researchers wrote in their paper, “but considering the vastness of the deep sea and the occurrence of luminous organisms in this zone, it is now more and more obvious that producing light at depth must play an important role structuring the biggest ecosystem on our planet.”

Together with Darren Stevens of the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) in New Zealand, they undertook a study of the mesopelagic sharks found in local waters.

Thanks to their work, we now know that the kitefin shark (Dalatias licha) – which has a global distribution – is indeed bioluminescent, something that scientists had suspected since the 1980s, although no clear evidence had been found.

The other two sharks, the blackbelly lanternshark (Etmopterus lucifer) and the southern lanternshark (E. granulosus), are much smaller than the kitefin, up to 47 and 60 centimetres respectively, but they’re also the most common shark by-catch species found in New Zealand deep-sea trawlers.

The scientists caught their specimens on a NIWA survey trawl of Chatham Rise off the east coast of New Zealand in January 2020. Of the hundreds of sharks caught, 13 kitefin sharks, 7 blackbellies, and 4 southern lanternsharks were used for the bioluminescence study.

In the skin of all three species, the scientists found photophores, a light-emitting organ found in bioluminescent animals.

Curiously, in sharks the light emission is controlled hormonally (the only known animal species for which this is the case). The researchers found that with their three shark species, melatonin triggers the glow, alpha-melanocyte stimulates it, and adrenocorticotropic hormones shut it down.

As for why the sharks glow, that is not quite so easy to ascertain. Mesopelagic animals can glow for many reasons: attracting a mate, luring prey, schooling, or camouflage.

The scientists think for their sharks it might be the latter reason. The glow is concentrated around the bellies and undersides, and in the mesopelagic, this could help make these fish virtually invisible from certain angles.

It’s not quite deep enough where the sharks hang out for no light at all to penetrate; to prey animals swimming underneath the sharks, they could appear silhouetted against the sky. But when their bellies light up blue, they would be much harder to see against the blue sky – a type of camouflage known as counterillumination.

That said, the glow on the dorsal fins of the kitefin shark is a little more difficult to puzzle out; more research into their behaviour is needed.

Understanding these creatures, the researchers said, could provide some insight not just into the individual species, but how the deep-sea ecosystem works as a whole.

“This first experimental study of three luminous shark species from New Zealand provides an insight into the diversity of shark bioluminescence and highlights the need for more research to help understand these unusual deep-sea inhabitants: the glowing sharks,” they wrote in their paper.

The research has been published in Frontiers in Marine Science.