As with weeds in a garden, it is a challenge to fully get rid of cancer cells in the body once they arise. They have a relentless need to continuously expand, even when they are significantly cut back by therapy or surgery. Even a few cancer cells can give rise to new colonies that will eventually outgrow their borders and deplete their local resources. They also tend to wander into places where they are not welcome, creating metastatic colonies at distant sites that can be even more difficult to detect and eliminate.

One explanation for why cancer cells can withstand such inhospitable environments and growing conditions is an old adage: What doesn’t kill them makes them stronger.

At the very earliest stage of tumor formation, even before cancer can be diagnosed, individual cancer cells typically find themselves in an environment lacking nutrients, oxygen or adhesive proteins that help them attach to an area of the body to grow. While most cancer cells will quickly die when faced with such inhospitable conditions, a small percentage can adapt and gain the ability to initiate a tumor colony that will eventually become malignant disease.

We are researchers studying how these microenvironmental stresses affect tumor initiation and progression. In our new study, we found that the harsh microenvironments of the body can push certain cancer cells to overcome the stress of being isolated and make them more adept at initiating and forming new tumor colonies. Moreover, these cancer cells may adapt even better in the inhospitable and stressful conditions they encounter while trying to establish metastases in other areas of the body or after they are challenged by treatment with chemotherapy or surgery.

The microenvironment of a cell can significantly influence its function.

Cancer cells overcoming isolation stress

We focused on pancreatic cancer,

one of the most lethal cancers and one that is notoriously resistant to chemotherapy and often not curable with surgery. Almost 90% of pancreatic patients will succumb to cancer recurrence or metastasis within five years after diagnosis.

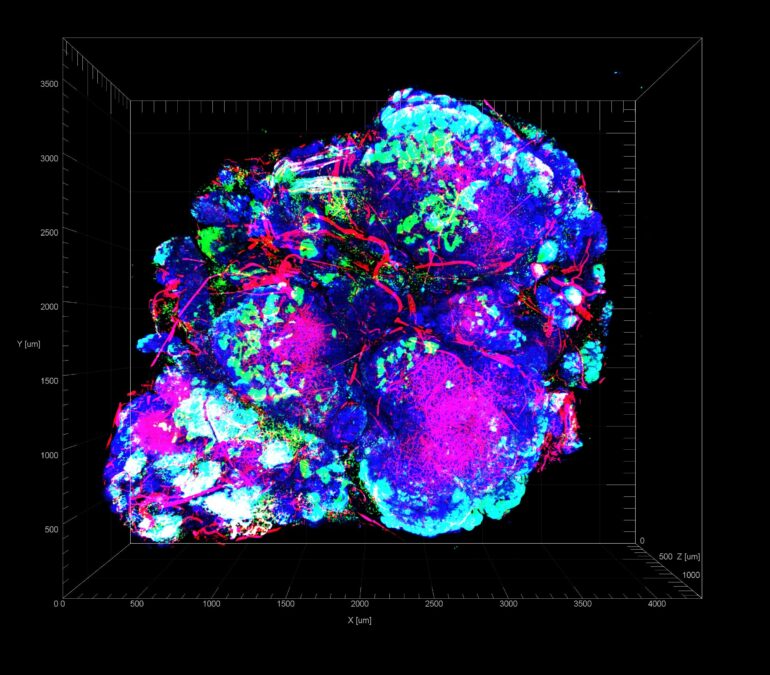

We wanted to study how tumor formation is affected by what we call “isolation stress, when cells are deprived of nutrients or oxygen supply because of poor blood vessel formation or because they cannot benefit from making contact with nearby cancer cells. To study how cancer cells respond to these situations, we recreated different forms of isolation stress in cell cultures, in mice and in patient samples by depriving them of oxygen and nutrients or by exposing them to chemotherapeutic drugs. We then measured which genes were turned on or off in pancreatic cancer cells.

We found that pancreatic cancer cells challenged with conditions that mimic isolation stress gain a new receptor on their surface that unstressed cancer cells don’t typically have: lysophosphatidic acid receptor 4, or…